Sustaining turtles and their homes

The project studied how sediments from dredging and discharges can affect sea grass and turtles.

The report quantified the risks to turtle populations from dredging and increased boat traffic.

Transcript for Tagging turtles video

[Title page appears with the following text: GISERA Gas Industry Social & Environmental Research Alliance]

[Music plays and a new title page appears with the following text: Marine Environment, Research Updates]

[Image changes to a zoomed out shot of a Marina. The camera then zooms in on a boat moving along the water]

[Image has changed to a man driving on boat on water]

Russ Babcock: We’re here in Gladstone, working on a project that’s looking at the marine ecosystem in the harbour around Port Curtis and trying to understand more about how it works so that we can try and bring about a better kind of balance between economic progress and the environment.

[Image of Russ Babcock, Principle Researcher, CSIRO, Marine & Atmospheric Research]

[Image changes to show scientist dressed in diving gear and entering the water to collect a turtle which he hands to a colleague still on the boat]

The turtles here in the harbour have been under pressure due to a range of factors, both natural and manmade.

[Image has changed back to Russ Babcock]

They’re an iconic species that everyone wants to try to look after and they’re sort of an indicator of the health of the ecosystem, because they’re dependent on seagrass which is right at the base of the food chain.

[Image changes to scientist underwater collecting a turtle]

So if we see something happening to the turtles we know that we’ve got to start thinking about what’s going on in the rest of the environment.

[Image changes to a shot of a dredger]

One of the other activities in Gladstone that potentially impacts on turtles is dredging.

[Image has changed back to Russ Babcock]

So dredging stirs up a lot of sediment and that can block out the light for seagrass and smother it and as seagrass is one of the main food sources for turtles, we need to know what the effects of dredging on seagrass are.

[Image has changed to Containment Floats]

Which parts of the harbour have been most effected and again how that interacts with the turtle’s use of the harbour.

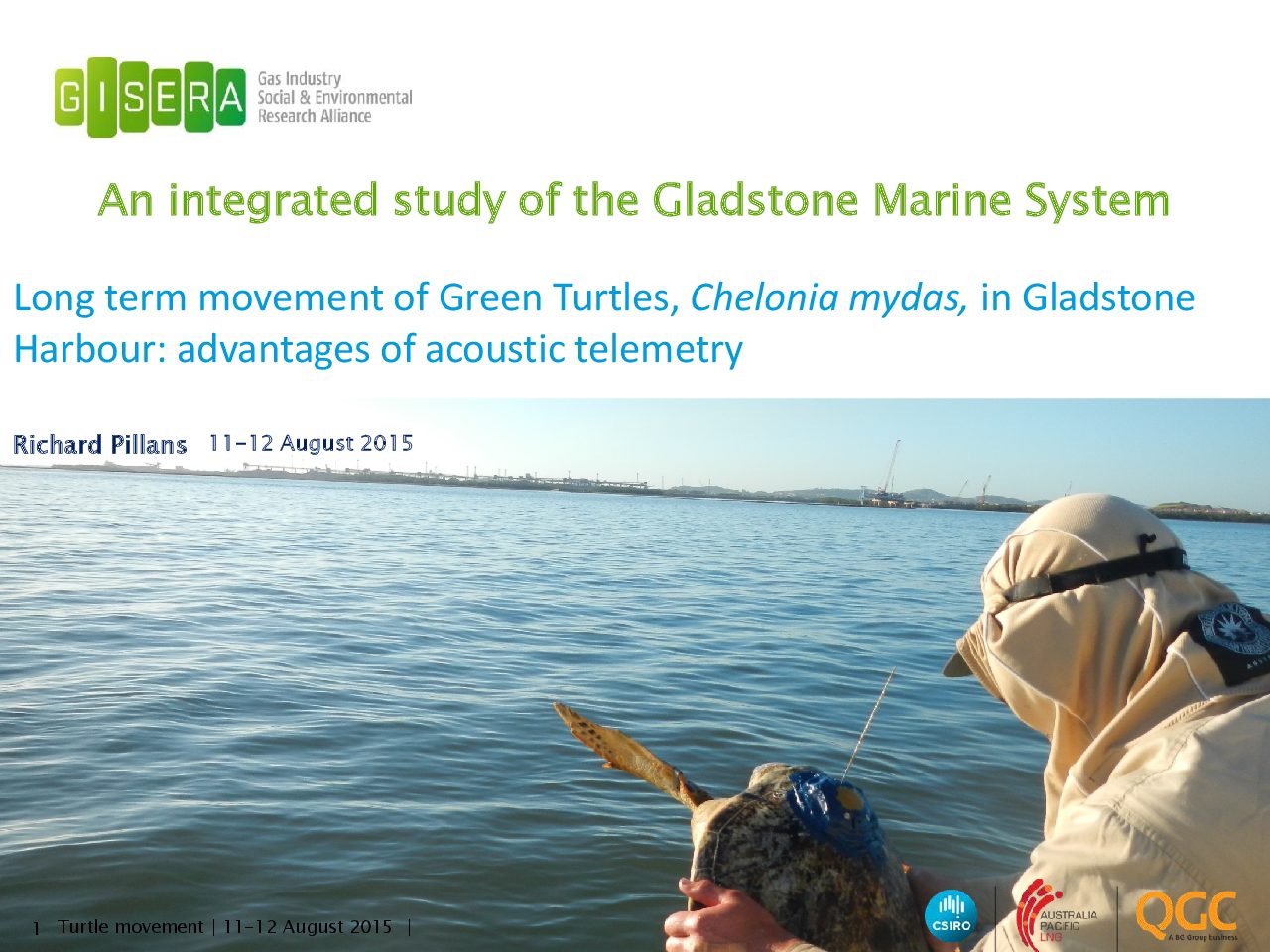

[Image changes to staff working on a turtle that’s laid out on the floor]

We are tagging these turtles with two types of technology. We’re tagging a small number of turtles with satellite tags; they’re going to tell us how well the other types of tags that we’re using are working.

[Camera zooms in on the turtle that is being fitted with a tag]

So these are smaller acoustic tags that can last for up to ten years.

[Image has changed back to Russ Babcock]

By studying the movements of these turtles and interpreting the data we get we’ll be able to identify feeding areas and also transit paths that turtles use to get from one part of the harbour to the next.

[Image has changed to show turtles on the boat being tagged]

[Camera zooms in a lady tagging a turtle and reading its serial number]

Female researcher: 36824.

[Image has changed back to Russ Babcock]

Russ Babcock: For example in the Moreton Bay Marine Park we’ve got go slow areas that are designated for boats to travel at a slow speed, so that they don’t run into turtles and dugongs. Similar things might happen in Gladstone Harbour, you know, if appropriate ways can be found to manage vessel movements and animal movements.

[Image changes to show the Starbug underwater]

We’ll be using the, a mini submarine, that’s going to give us a picture of, not only what’s present in terms of seagrass, but also how much sediment is in the water, what the salinity and temperature is, dissolved oxygen – a whole range of features that can help us interpret what’s going on in the environment. [Image changes back to staff taking a sample from a turtle and then measuring one that’s on the ground]

So we’re taking samples of many different kinds to look at the reproductive status of the turtles, their health in terms of what’s the composition of their blood.

[Image changes to show someone recording that data onto a board]

And from samples that we take we can also tell something about the diet of the turtle over, not just the past few days, but also over the months previous. [Image has changed back to Russ Babcock]

So it gives us a multilayered picture of the health of the turtles, how they use the environment and then we can link that to our tracking studies that tell us where the turtles are going and which parts of the harbour they’re moving into.

[Image changes to show a big turtle being lifted from the ground in a harness and laid down onto a research boat, which is towed away by a vehicle]

But there are still a lot of unknowns in terms of how long turtles stay in the harbour, what they’re doing while they’re here and how their movements might interact with the human activities in the harbour.

[Image changes to show different parts of the harbour]

Industry and environment are both here to stay. If we’re going to have both of them coexisting in a hundred years’ time, we have to start putting in the work now. The more we know about the parts of the harbour that the turtles use the better we’ll understand how future development in the harbour can be managed to minimise any harmful effects on turtles.

[Image changes to show a turtle underwater eating seagrass]

[Music plays and a title page appears with the following text: GISERA Gas Industry Social & Environmental Research Alliance]

Tagging turtles – GISERA video