Putting land management knowledge into practice

Research from around the world identifies unsealed roads in agricultural and rural regions as a major source of sediment being washed into waterways – up to 40 per cent of sediment loads, even though they occupy as little as one to two per cent of the landscape.

In the onshore gas development regions in Queensland’s Surat Basin, a network of access tracks traverse farmland to provide access to coal seam gas wells.

In proposed onshore gas development regions in New South Wales and the Northern Territory, similar access requirements will need to be negotiated with landholders should those development proposals proceed.

unsealed roads in agricultural and rural regions as a major source of sediment being washed into waterways

Unsealed roads in agricultural and rural regions can be a major source of sediment being washed into waterways.

The science of effective land management

For CSIRO scientist Dr Neil Huth, it’s vitally important that the lessons of effective land management developed in Queensland – including sensitive location of roads and other gas development infrastructure – are incorporated into any new development.

This is particularly true for the Pilliga Forest in NSW, and the fragile soils of the Beetaloo Sub-basin in the Northern Territory.

Neil leads a CSIRO research team that has been using digital technologies to quantify and communicate impacts of gas development on grazing lands over the past six years.

This work has been carried out through CSIRO’s Gas Industry Social and Environmental Research Alliance (GISERA).

Neil said that gas companies were acutely aware that maintaining access roads was a constant and costly challenge, and one that had to be managed well in order to maintain good relations with landholders.

“Several years ago, the Queensland gas companies came to us and said that they were experiencing challenges in maintaining roads, and that it was costing them a lot of money and time,” Neil said.

“This was a landscape-scale issue, very widely dispersed, so using high-precision digital photography and computing power we built a three-dimensional model of 1,200 square kilometres of gas development.

“This model allowed us to determine the soil surface elevation every 20 centimetres. And then we did that multiple times so we could see how the soil surface was changing over time during gas development.

“Now that we have a virtual world, we can simulate virtual rainfall across it and map where the water flows, so that we could see how gas development would change the water flows across the landscape.”

Neil said the 3D model provided landholders and gas companies with compelling visual information that supported discussion and negotiation over placement of infrastructure in locations to minimise erosion.

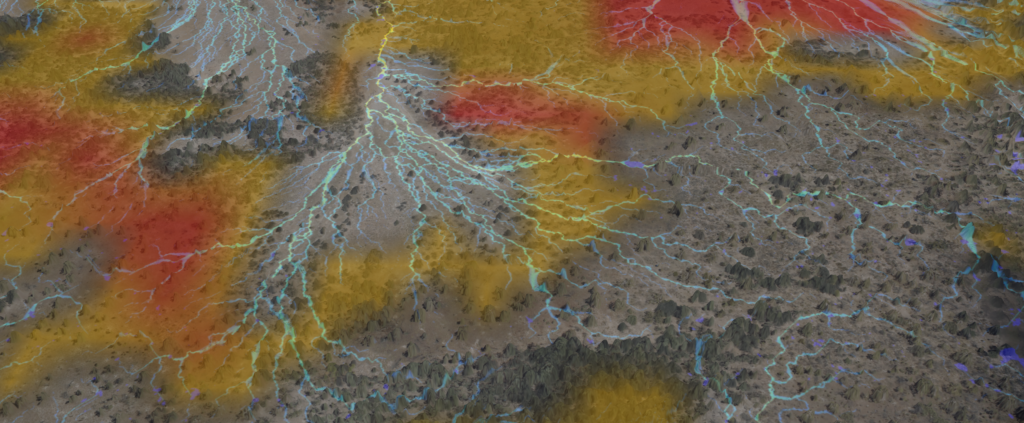

CSIRO map of overland water flow.

CSIRO map of virtual overland water flow. Farmers, land managers and gas companies can use this information to understand erosion risks, and to develop solutions.

Inside the herd

In other research, Neil’s team used tracking devices to understand how cattle interacted with pipelines, access tracks, gas wells and other infrastructure located on farmland.

“We put GPS collars on cattle to monitor where they went, what they did, and also how they interacted with CSG infrastructure onsite.

“When the cattle were released, we found they spent a disproportionate amount of time on pipelines and around CSG infrastructure.

“We can use this data to create grazing ‘heat maps’ showing where most of the cattle spend most of the time.”

When combined with the water flow models, these heat maps identified areas in the landscape that were subject to the combined pressures of overgrazing, soil disturbance and water erosion, which has a damaging multiplying effect.

“Having access to this information allows landholders and gas companies to work together to address these problems and to minimise or even avoid the erosion issues through better planning.”

Tracking cattle movement with GPS collars.

Tracking cattle movement with GPS collars.

Telling the story

To take the science out of the laboratory and into the hands of farmers, landholders and gas companies, Neil’s team is working with a technology company to make erosion maps more easily available.

Neil’s team also spent considerable time talking with farmers, community groups and gas companies to explain the research and how the science can be used to create better outcomes on the land.

“We spent a lot of time engaging, whether it was at workshops or at kitchen table sessions where you visit a farmer and you sit with a cup of tea and the maps are on the table, talking about erosion issues,” Neil said.

“Probably the most effective engagements were at local agricultural shows where you meet all levels of government, academia, industry, agriculture, and just mum and dad farmers, and spend half an hour to an hour talking to them about all of the science.”

Explaining science at agricultural shows.

Explaining the science of effective land management at agricultural shows.

Read more about Inside the herd and opportunities for CSIRO’s erosion mapping work in the Northern Territory.